International health officials are scrambling, without much success, to find meningitis C vaccines as an outbreak of the child-killing disease threatens to balloon into an epidemic.

The first large-scale outbreak of the C strain in decades has this year killed 800 of 12,000 infected people in Nigeria and in neighboring Niger, according to the World Health Organization.

In 2013 and 2014, deaths numbered 128 out of 2,046 people who fell ill, WHO said, indicating the infection rate has soared and could grow much higher in 2016.

"We've never seen this before with meningitis C," William A. Perea, coordinator of WHO's Control of Epidemic Diseases Unit, said of the resurgence of the strain.

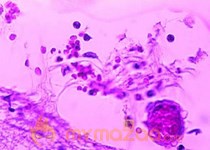

The bacterial infection mostly targets children, inflames the brain and spinal cord and kills half those infected if left untreated. Survivors can suffer brain damage, deafness, constant fatigue and neurological and emotional difficulties.

West Africa's biggest epidemic, in 1996, hit four countries, infected a quarter million people and killed 25,000. It was caused predominantly by meningitis A.

Since 2010, the meningitis A conjugate vaccine - used across 15 sub-Saharan countries in the "meningitis belt" stretching from Senegal in the west to Ethiopia in the east - has reduced infection rates. But it does not protect against the equally deadly C strain.

WHO, and partners including Doctors Without Borders, say they want to build a 5 million-dose stockpile before next year's meningitis season, which runs from January to June during the dry hot months that force people indoors and enable transmission.

While the Indian-manufactured meningitis A vaccine costs around 60 cents, the conjugate vaccine for meningitis C used in the United States costs $30 to $100 a dose. Two doses for babies provide 10 years' protection.

A much cheaper polysaccharide vaccine, produced for travelers, likely will be used as a stop-gap in West Africa. But that vaccine doesn't work for children under 2 and lasts only around two years.

At the start of the last meningitis season in January, only 200,000 meningitis C doses were available for the region, according to Myriam Henkens, international medical coordinator of Doctors Without Borders. By end of the season, in June, international agencies had sourced 1.6 million.

This month, WHO urged manufacturers to increase production. "The first round of discussions, (manufacturers) said no, we just can't produce any more," said Perea.

Major manufacturer Sanofi Pasteur has halted production to upgrade facilities and cannot restart until year's end, according to one of the French-based company's vice presidents, Michael Watson. He said they are one of only four global vaccine producers.

"You can't just turn on the tap," said Watson.

Nigerian health leaders have repeatedly asked the government to reopen a vaccine lab which once produced millions of vaccines for yellow fever, rabies and smallpox.

With a domestic market of 170 million people, "in Nigeria it makes a lot of sense," Watson said. "They have a population that justifies it."

In the late 1970s, Nigeria's laboratory made millions of smallpox vaccines that helped eradicate the disease regionally, according to Felix Nwabueze, who was a quality control officer. The lab fell into disrepair under the neglect of corrupt government officials.

"It would be more cost-effective if vaccines were produced in country, and would create employment," said Godswill Okara, former head of the Association of Medical Laboratory Scientists.

Abdulsalami Nasidi, who headed the lab in the 1980s and now is director of Nigeria's Center for Disease Control, fears the potential fatalities if a vaccine shortage and meningitis epidemic collide.

"But we are worried about the paucity not just of the meningitis C vaccine but other vaccines," he added. "Maybe this will teach us a lesson, to really address the local manufacturing issue."